Blog

30 April 2025

An Indian and a European pit their wits at chess while smoking on hookahs; the horizon bristles with shipping. Charles Gold, 'Oriental Drawings' (1806)

A number of the illustrated books in Emmanuel’s collection are based on sketches made by army officers: observant by profession, schooled in drawing as a means of record, and often reflecting contemporary tastes for the picturesque in both landscape and humankind. Of such books, Charles Gold’s Oriental Drawings (1806) is now both enjoyable and difficult. Based on Gold’s sketches made between 1791 and 1798, while he was a captain in the Royal Artillery in southern India, it is fascinating for its European take on the culture that it records, yet at the same time painful in its condescension to aspects of that culture.

Gold was in India in the latter stages of a series of conflicts between British forces and the southern kingdom of Mysore, under its charismatic ruler, Tipu Sultan (1751-1799).

'Mysorean cavalry attacked by British dragoons'

'Artillery Elephant'

Gold sketches what he calls an ‘artillery elephant’, who is giving a useful nudge with its trunk to help a cannon up a long incline. Prints of Gold’s drawings are etched almost entirely in aquatint, and this gives the prints a soft tonal quality.

Gold was evidently very interested in Indian customs, ceremonies and architecture.

He depicts what he terms the ‘colossal idols near Manapar’, with an elephant processing past and locals prostrating themselves on the ground.

'Colossal Idols near Manapar'

'Festival of the Chariot'

He sketches a striking image of the Festival of the Chariot, where a towering festive float is being dragged along. Both plates, like all the images, are accompanied by explanatory and historical essays.

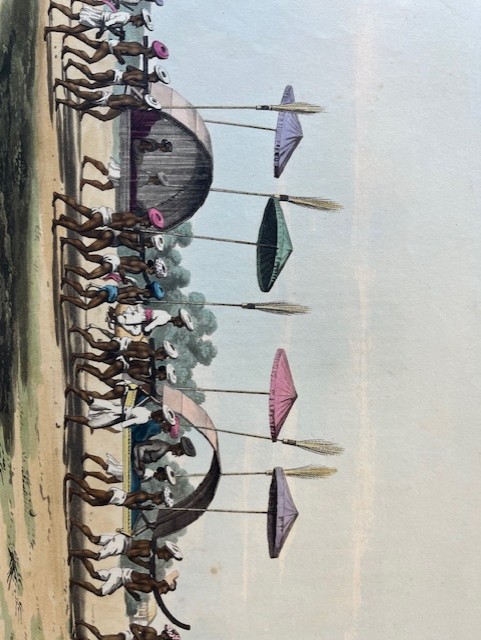

Processions and modes of transport are another interest, including a wedding procession: ‘This is an actual representation of the procession of a bridegroom and bride through the town of Negapatnam, where the sketch was made in 1795’.

'A Wedding Procession'

'Palankeens'

Another plate shows the convenient custom of the palanquin, a kind of enclosed chair carried by retainers.

Gold even attempts, rather enterprisingly, to put down on paper the complete chaos of a typhoon.

Typhoon

'Flying Foxes'

But Gold’s depiction of flying foxes, with a red-coated British officer holding one that he has shot, as if he were shooting pheasants at home, introduces an insensitive note, set alongside the sacred banyan tree with an Indian seated beneath it in contemplation.

As well as an eye for the aesthetics of Indian architecture, Gold evidently had, more unusually, a real fascination with Indian music, recording local musical instruments and performers. But, perhaps inevitably in a book of travels, he tends to emphasize the bizarre for his readers, depicting ‘snake charmers with serpents dancing to music’, and a ‘Hindu juggler’ performing a sword-swallowing trick.

'Snake Charmers'

'Hindu Juggler'

However, Gold’s portrayals of ordinary Indians, including the indigent and beggars who so often caught his attention, tend too often to the cartoonish.

For Gold, the extremes and sheer intensity of some Indian religious culture was fascinating but horrible. He records a general view of what he terms a ‘barbarous ceremony, in honour of Mariatale, Goddess of the Smallpox’, which involves being suspended in the air by hooks eating into the flesh. And Gold provides a close-up too, showing the hooks implanted in the devotee’s back.

'Barbarous Ceremony, in honour of Mariatale, Goddess of the Smallpox'

Detail of Devotee

There is a comparably horrified fascination with how a zealot goes on a pilgrimage which he makes by rolling over the dusty ground, nearly naked, for long distances.

Gold notes that since this zealous pilgrim is a man with resources, he employs a team to prepare his way and move any obstructions to his rolling along. Try it?

'A Zealot'

Gold’s depiction of Tipu Sultan’s palace, with a vast procession forming up, catches something of the impression on contemporary British observers made by the splendour and ceremony of India. The Sultan will lead the procession. He will be preceded by attendants, mounted on camels and beating on kettle drums, while they proclaim the titles and surpassing qualities of their lord.

'Tipu Sultan's Palace'

'Tomb of Hyder Ali'

Soon after, near the end of his book, comes Gold’s appreciative depiction of the exquisite tomb of Tipu Sultan’s father (and eventually of himself). The tomb was disgracefully desecrated by British troops, and Gold’s text includes a kind of embarrassed mumble regretting this as a military necessity in a strategic spot. It is an aptly mixed conclusion to these vivid but sometimes uncomprehending images made by a European of late eighteenth-century India.

Barry Windeatt, Keeper of Rare Books